How I found my first CVE (CVE-2025-8447)

I’d always been interested in bug bounty and I REALLY wanted a CVE for nerd cred. However, I always struggled with confidence and sticking with it due to loads of impostor syndrome.

Earlier in the year I found a bug in Windmill that ended up flying under the radar and not getting a CVE. The excitement of finding that bug and not getting a CVE drove me to really try and find one.

So I discussed with some of my colleagues and they pointed out that GitHub was a good program to hack on. Supposedly good response times, good payouts, and a product I like using, so it was a no-brainer for me.

The Official Description Vulnerability

The bug was assigned CVE-2025-8447.

An improper access control vulnerability was identified in GitHub Enterprise Server that allowed users with access to any repository to retrieve limited code content from another repository by creating a diff between the repositories. This vulnerability affected all versions of GitHub Enterprise Server prior to 3.18, and was fixed in versions 3.14.17, 3.15.12, 3.16.8 and 3.17.5.

The Journey

So after some digging and discussing, it was brought to my attention that GitHub Enterprise Server is sort of open source. A friend told me you can visit the enterprise server downloads page and grab the latest copy. The code is present on the enterprise obviously, but what was surprising to me, was that it was all in ruby and readable thanks to some deobfuscation scripts. I’m an appsec guy, so I’ll always take source whenever I can get it. Armed with full source access to GitHub Enterprise Server, I embarked on my first serious attempt at bug bounty.

After getting that set up and running on a spare laptop (this VM seriously takes 30gb of ram), I started poking at the server and reading, trying to get a feel for the code. Whenever I start diving into a codebase, I always invest a little time into determining how to efficiently map the external inputs and endpoints I’m seeing while using the application, to the lines of code processing them.

Once comfortable, I spent a few weeks on the email verification flow. I found an interesting issue that was ultimately deemed not exploitable. Luckily, this time wasn’t wasted because I further built up my knowledge and “feel” for the codebase I was interacting with.

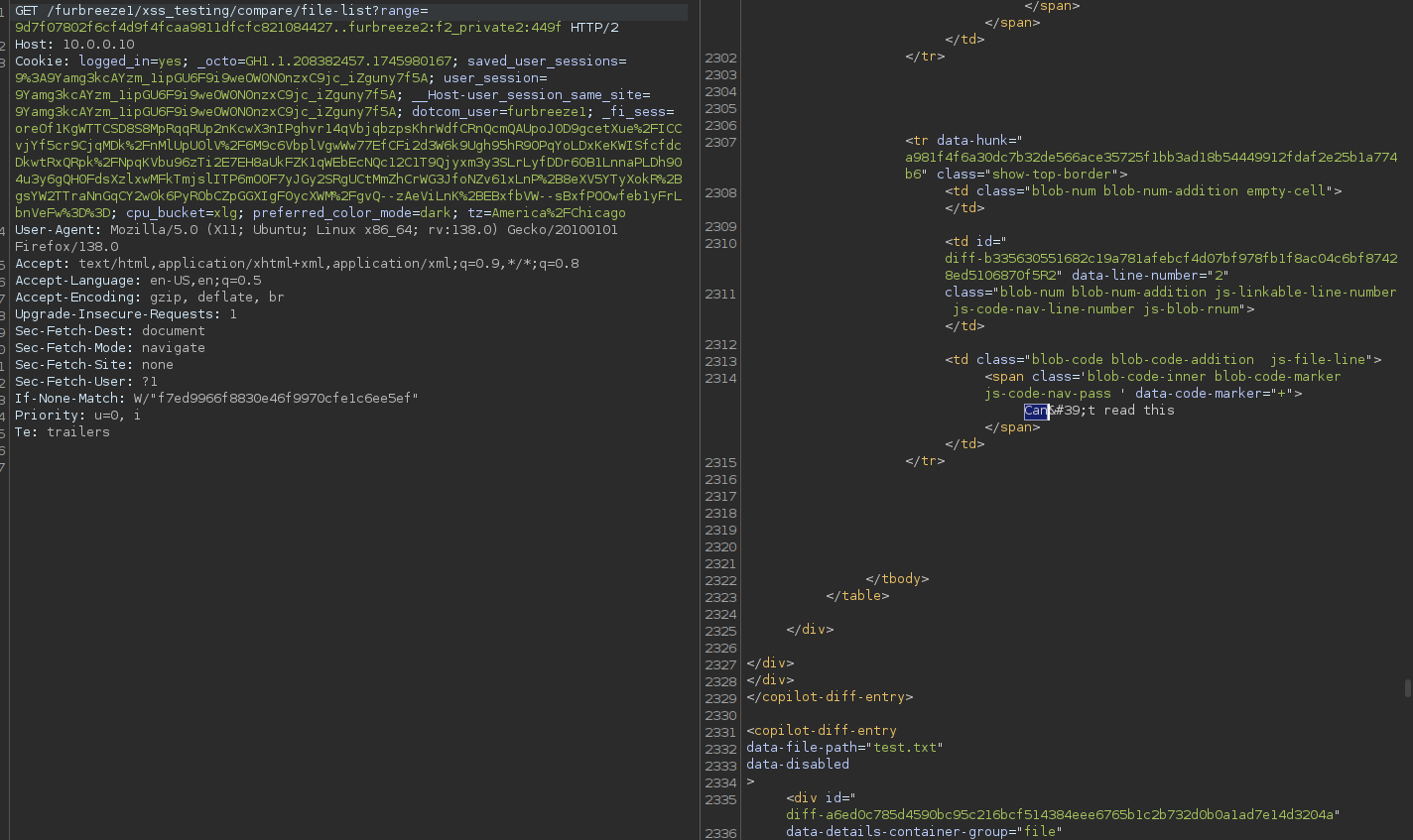

After the email issue, I needed a fresh perspective so I just started using the application again. While browsing through functionality in the repositories, I noticed something odd: A ... in the request to compare two commits. My brain immediately said “That’s not a normal web convention, there’s some custom parsing going on… I wonder what they’re doing there?”.

Further investigation in the source revealed that they were taking a few different inputs and mapping them to various repositories, users, and commits. What’s more, I was able to determine the full format of the payload, listed below:

https://<enterprise_url>/<your_username>/<your_repo>/compare/file-list?range=main...<other_user>:<their_private_repo>:<four_characters_of_a_commit_hash>

Additionally, there was a different code path I could reach by using .. instead of .... What was interesting about the .. format, was that I could control the source and destination repository. Specifically, I could compare a repository I owned to any other repository, even one I didn’t own. Surely this couldn’t be true, right?

Well I fired up burp and it really was that easy :) Just a plain old IDOR sitting there looking right at me.

Well this is exciting, I have a bug! What did I need to exploit it?

- An account on a GHE server

- The repository name

- The username of the repository owner

- A branch name

- A commit hash to diff to and leak from

Looking at the above list, quite a few of these are “given”. This attack assumes you already have an account on the GHE instance. Additionally, you’re usually safe to assume the branch name will be main, master, or production, for most usecases.

One way to get a repository name is to initiate a transfer request between two users. If the user you’re transferring to has a repository of the same name, the system will throw an error indicating they already have repository of that name.

Finally, it is common for private repository names, usernames and organizations to be leaked in source code, commits, etc. which can be found through normal use of the application.

With those out of the way, it’s onto the more challenging part, how do you leak a commit hash? This is a SHA-256 hash, so brute force guessing it is not going to work. Or is it…?

After poking at the endpoint some more, I noticed that the endpoint only actually requires the first 4 characters of the commit hash. Armed with that knowledge, we’ve drastically reduced the brute force space to 65536 (16^4) guesses, and since there are no brute force protections in a standard deployment… EZ PZ. It should also be noted that this implies there’s only ONE commit on the repo. The search space drastically reduces further the more commits that have been performed in the repo.

Tying all of this together, we finally arrive at full arbitrary read of any repo in the GHE instance, only requiring a valid user account. For the record, I don’t know why this only worked on GHE and not on github.com. I have to assume the codebases are a little different and this happened to be a feature where it was.

Beyond the Official Description

retrieve limited code content from another repository

This was untrue by following the following algorithm:

- Perform diff

- Update attacker repo to contain leaked contents

- Goto 1

This was communicated to the team, however it did not affect the final severity.

Impact

The vulnerability could allow unauthorized users to access code they shouldn’t have permission to view, potentially exposing sensitive information or intellectual property stored in private repositories.

Remediation

GitHub fixed this vulnerability in the following versions:

- 3.14.17

- 3.15.12

- 3.16.8

- 3.17.5

All users of GitHub Enterprise Server should update to these versions or later to protect against this vulnerability.

Timeline

- Issue Reported May 3rd 2025

- Issue Triaged July 22nd 2025

- Issue Awarded $10k bounty August 26th 2025

- Issue Marked as Resolved August 26th 2025

- Issue Disclosed Sept 23rd 2025

Lessons Learned

I heard a quote from a bug bounty podcast, “Big Cheese, Big Holes”, which really stuck with me. I think I had success here because I was willing to look at a big target like GitHub, something plenty of people hack on, and approach it with an open mind, positivity, and curiosity. In the future, I think keeping that positivity will be just as important as any skilling up I can possibly do. Especially when going after more big targets.

Finally, Bug bounty requires PATIENCE, an attribute I am admittedly lacking in. It was my first real bug submitted and waiting for everything to shake out was BRUTAL.

Next steps

Good news, there’s a sequel :) I will disclose more when I can.